Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe.Good morning ladies and gentlemen.

We are here at Ashdown House and Hammerwood Park today because of the work of

Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

The Architectural Historian James Stevens Curl has described these houses as "the most remarkable houses for their date in the British Isles". Not only are they special in themselves but they are a landmark in the development of world architecture.

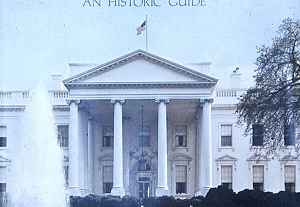

Whenever Americans look at their banknotes, they see  an image of their inheritance from Benjamin Latrobe.

an image of their inheritance from Benjamin Latrobe.

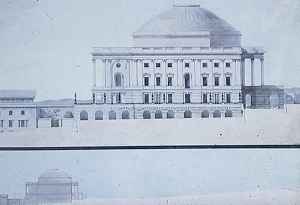

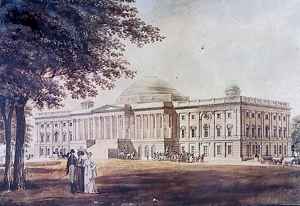

He was responsible for the building of their Capitol building  and the porticos

and the porticos  of the President's House.

of the President's House.  It is the image of this building, above all, that conjures up in our minds

It is the image of this building, above all, that conjures up in our minds  the presence of the President of the United States of America. We will see today how this was derived directly from these two buildings in Sussex which host our meeting today.

the presence of the President of the United States of America. We will see today how this was derived directly from these two buildings in Sussex which host our meeting today.

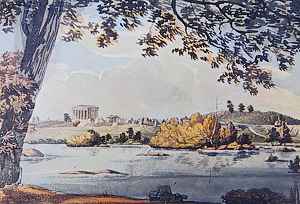

I have a passion for drawings of buildings set in landscapes with a single tree on the left. This one is of Athens of the 18th century showing the Parthenon at the top of the Acropolis. This particular building is just as much one of my obsessions as is Hammerwood itself. By reason of Latrobe's understanding of symbolism, I am sure that he would have approved. Unfortunately, however, we will not have time to explore these areas today.

I have a passion for drawings of buildings set in landscapes with a single tree on the left. This one is of Athens of the 18th century showing the Parthenon at the top of the Acropolis. This particular building is just as much one of my obsessions as is Hammerwood itself. By reason of Latrobe's understanding of symbolism, I am sure that he would have approved. Unfortunately, however, we will not have time to explore these areas today.

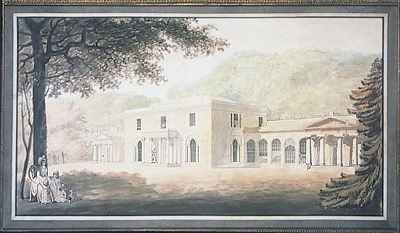

But this drawing reminds us of the domination of the influence of travel in the 18th century and the inspiration of the European Grand Tour. We know that Latrobe went as far south as the bay of Naples in Italy and  in this drawing of Richmond in Virginia we see the influence of Latrobe's understanding of the principles of the Picturesque gained on his European travels.

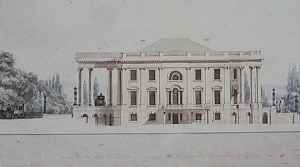

in this drawing of Richmond in Virginia we see the influence of Latrobe's understanding of the principles of the Picturesque gained on his European travels.  We see here another drawing with a tree on the left of a building that you will recognise in Washington. The drawing is dedicated to the President Jefferson. And here,

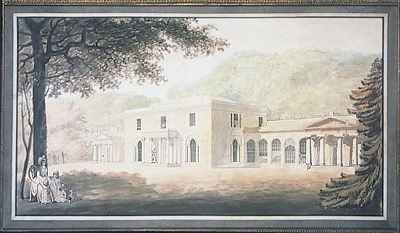

We see here another drawing with a tree on the left of a building that you will recognise in Washington. The drawing is dedicated to the President Jefferson. And here,  in a similar style we see Latrobe's very first perspective drawing dedicated to a client for a house to be built in 1792.

in a similar style we see Latrobe's very first perspective drawing dedicated to a client for a house to be built in 1792.

It is an extraordinary drawing, especially considering the work which was to flow from it.

The client, John Sperling, is shown in the centre with hunting gun in hand and his hunting dog at his feet. He stands in a portico at the front door of his new house and his wife sits at the side in the shade of a tree. She is surrounded by her children in domestic bliss. The house is wonderful and the detail of the drawing is superb. See the details on the temple on the right, the plaque above the door, and the shadow of the sun of the capitals of the columns falling over the small section of fluting at the top of the columns which is so particularly delineated.

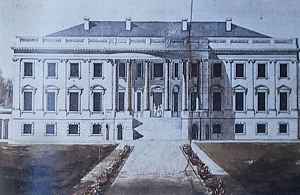

We have not time to examine this drawing in detail, but looking at the first building which derived from it, we find  not only a building with a tree on the left, but

not only a building with a tree on the left, but  a house built strangely the same but different. There is no front door: instead the drama of giant pilasters to look like columns.

a house built strangely the same but different. There is no front door: instead the drama of giant pilasters to look like columns.  It is necessary to see the house from the original road to see Latrobe's creation in the perspective which he was to achieve.

It is necessary to see the house from the original road to see Latrobe's creation in the perspective which he was to achieve.  These columns were originally white - a limestone - and from a distance

These columns were originally white - a limestone - and from a distance  they dominate the facade.

they dominate the facade.  We see the temples on the wings as echoes of the central columns and because we see the temples smaller, we assume that they are set back much more than they are. Latrobe has created drama as well as a trick of the eye.

We see the temples on the wings as echoes of the central columns and because we see the temples smaller, we assume that they are set back much more than they are. Latrobe has created drama as well as a trick of the eye.

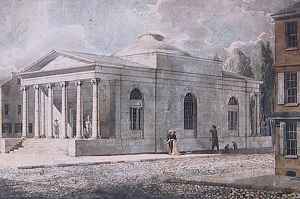

But this left part of Latrobe's drawing unbuilt. Enter our hero Trayton Fuller, a nephew of famous "Mad Jack" of Brightling, who was to rescue Latrobe's unbuilt house from the centre of the drawing.  Here we are, at Ashdonw House built in 1793. Do you remember the square portico in which John Sperling stood?

Here we are, at Ashdonw House built in 1793. Do you remember the square portico in which John Sperling stood?  Here it is but transformed into a semicircle . . .

Here it is but transformed into a semicircle . . .

So let us combine now  the round portico of Ashdown House with the drama which was achieved

the round portico of Ashdown House with the drama which was achieved  at Hammerwood

at Hammerwood  with columns double height and

with columns double height and  here we have The White House.

here we have The White House.

Whilst Hammerwood achieves its fundamental drama from a distance, Ashdown is feminine  and desires us to admire its details.

and desires us to admire its details.  As we are led in we are required to look up into this trompe l'oeil dome. This heralds

As we are led in we are required to look up into this trompe l'oeil dome. This heralds  Latrobe's Baltimore Cathedral and

Latrobe's Baltimore Cathedral and  the Bank of Pennsylvania immortalised by

the Bank of Pennsylvania immortalised by  his 1798 drawing of the angel of Architecture.

his 1798 drawing of the angel of Architecture.

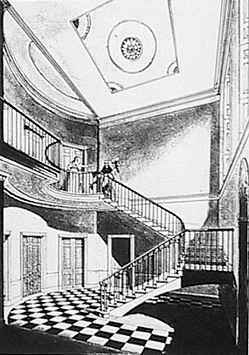

We arrive inside and find his very sophisticated use of spaces

We arrive inside and find his very sophisticated use of spaces  to be echoed again in the Pennock house in the United States. We climb the stairs and, again, are impressed by his sophisticated use of space,

to be echoed again in the Pennock house in the United States. We climb the stairs and, again, are impressed by his sophisticated use of space,  compounded by mirrors in which we see windows in walls where we least expect.

compounded by mirrors in which we see windows in walls where we least expect.

When we go into the Ballroom of Hammerwood  we find a sophistication in just the same way and again with th euse of mirrors to reflect windows where we least expect.

we find a sophistication in just the same way and again with th euse of mirrors to reflect windows where we least expect.

The interior of Hammerwood is easily eclipsed by  the exterior which overwhelms our impressions.

the exterior which overwhelms our impressions.

In both houses the drama, as we shall see, is in the approach and entrance. At Ashdown this is in the interior and the entrance hall as we have seen, whilst at Hammerwood this is on the exterior.

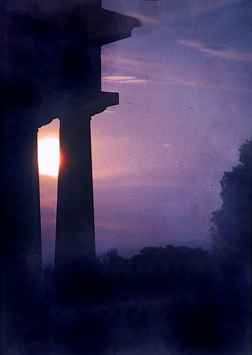

These entrance porticos  (here seen in extreme evening light) demand our attention by their strangely primitive columns

(here seen in extreme evening light) demand our attention by their strangely primitive columns  signed

signed  by their maker

by their maker  and

and  inscribed in Greek

inscribed in Greek  in honour of Latrobe himself.

in honour of Latrobe himself.  Pictures above

Pictures above  the doors require our entry and indicate what we might find inside.

the doors require our entry and indicate what we might find inside.

It has been easy in the last century to overlook Hammerwood, overgrown

It has been easy in the last century to overlook Hammerwood, overgrown  and

and  left derelict and

left derelict and  neglected. Its face appeared ugly and its charms appeared hard to find.

neglected. Its face appeared ugly and its charms appeared hard to find.  But once revived it becomes apparent

But once revived it becomes apparent  that there is nothing else like it on earth and

that there is nothing else like it on earth and  the light rises. It is an intimate part

the light rises. It is an intimate part  of our landscape, an

of our landscape, an  underappreciated part of our country and

underappreciated part of our country and  our heritage, without which mankind would be the poorer without the work of Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

our heritage, without which mankind would be the poorer without the work of Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

Copyright David Pinnegar June 2nd 2001